No Aboriginal Disadvantage

My people are from northern New South Wales, and although I work in Sydney as the Sydney Opera House’s Head of Indigenous Programming, I am a non-traditional fly-in-fly-out worker. I am a Widjubal woman and I live most of my week on country with my roots firmly planted in the rich fertile soil and the sweet waters of the mountains-to-saltwater country of the Bundjalung east coast territories.

As I sat down to write this piece, what came to me first was something that my colleagues have said about Homeground, our annual celebration of First Nations history and culture at the Opera House. They said “let’s make sure we don’t show it as worthy, dark, gloomy or educative.” I said, well, that’s bloody easy to do – because black isn’t black.

A recent scientific study has provided DNA evidence that Indigenous Australian society is the most ancient civilisation on earth. This is backed up by the generally-held belief that Australia’s first people are the oldest living, adapting culture – we even survived an ice-age.

Some Australians might find this evidence unsettling, but like Larissa Behrendt, I say “I told you so”.

Larissa Behrendt, Indigenous advocate, film maker and writerIndigenous Australians know we’re the oldest living culture — it’s in our Dreamtime.

We have over 700 languages and dialects and a rich history of oral storytelling – but what is important is the harmonious way in which we connect to country and our place in the cosmos. We are caretakers. We express this harmonious relationship and cultural awareness in science, story and song.

It’s there in the word “Eora”, which we associate with the nation group around Sydney and which means “here” in the local Dharug language. “I come from here” – no name, it was just their country, that’s how connected they were to it.

It’s easy to see nothing but negativity: colonisation, destruction of our land and intergenerational trauma after successive government interventions, not to mention the cruel old stereotypes that still pervade mainstream media. But I say there is no Aboriginal disadvantage – our culture is our advantage.

Actually, it’s an advantage that all Australians share and can become our shared strength.

But the progress feels too slow on the football field and in the classroom. Can sharing our culture – the giving and receiving of ancient dance and song – begin to heal the wounds inflicted over the last 230 years?

I believe the answer is yes. To share and celebrate First Nations culture together can be a path to a shared future and I’ve continued to turn that belief into action for many years. Homeground is but one manifestation.

Listening to a band, hearing about the cosmology or weaving with lomondra grass, we understand that the biodiversity, the science, the story and the song are all connected in a giant jigsaw and that without each of them nothing exists.

Today, we have less time to reexamine and reevaluate our place in the world – the big questions – the why. We are too busy on Twitter to listen to one another, country and the world around us.

As Australians, when we think deeply about our connection to the land, we can only be led by Australia’s first people. Spirituality is intrinsic in our songlines and in all the ways that these are expressed – yes in song, but also in dance and through visual arts.

My personal totem is the bimbul, the hoop pine. In Aboriginal culture you don’t just protect your totem, you become it. I have become strong, tall and unwavering in my commitment to sharing and promoting Indigenous culture as the pine continues strong and proud in my country.

A corroboree is a gathering – actually, the best corroborees are great big parties – with music, singing, authentic storytelling and dust clouds rising from thousands of feet stamping. In the old ways, our people would gather for tournaments, sporting events, festivals, marriages. We would travel to neighbouring clans for events, because the moiety stretches to the Sunshine Coast. We’d celebrate food sources like the bunya nut or down south it was the abundance of the bogong moth.

When I was 10, a big corroboree was held in Lismore. According to a Northern Star report at the time, some 10,000 people witnessed the continuance of the Widjabul song cycles led by my family. Witnessing a corroboree at a young age, knowing the chants and calls were thousands of years old, had a profound effect on me.

The best part about corroborees is the strength in numbers – the hearts, the souls and the minds brought together for one moment in time.

Our brains are wired to socialise and opportunities to connect with each other in shared celebratory experience are vital to harmonious living.

Perhaps this is why the corroboree has always been such a strong part of Indigenous Australian culture; as the oldest living culture on the planet we must’ve been doing something right?

In hindsight I marvel at the resilience of my family and their visionary approach to ensure our language, songs and stories were laid down in the archives so they would always be available for future generations.

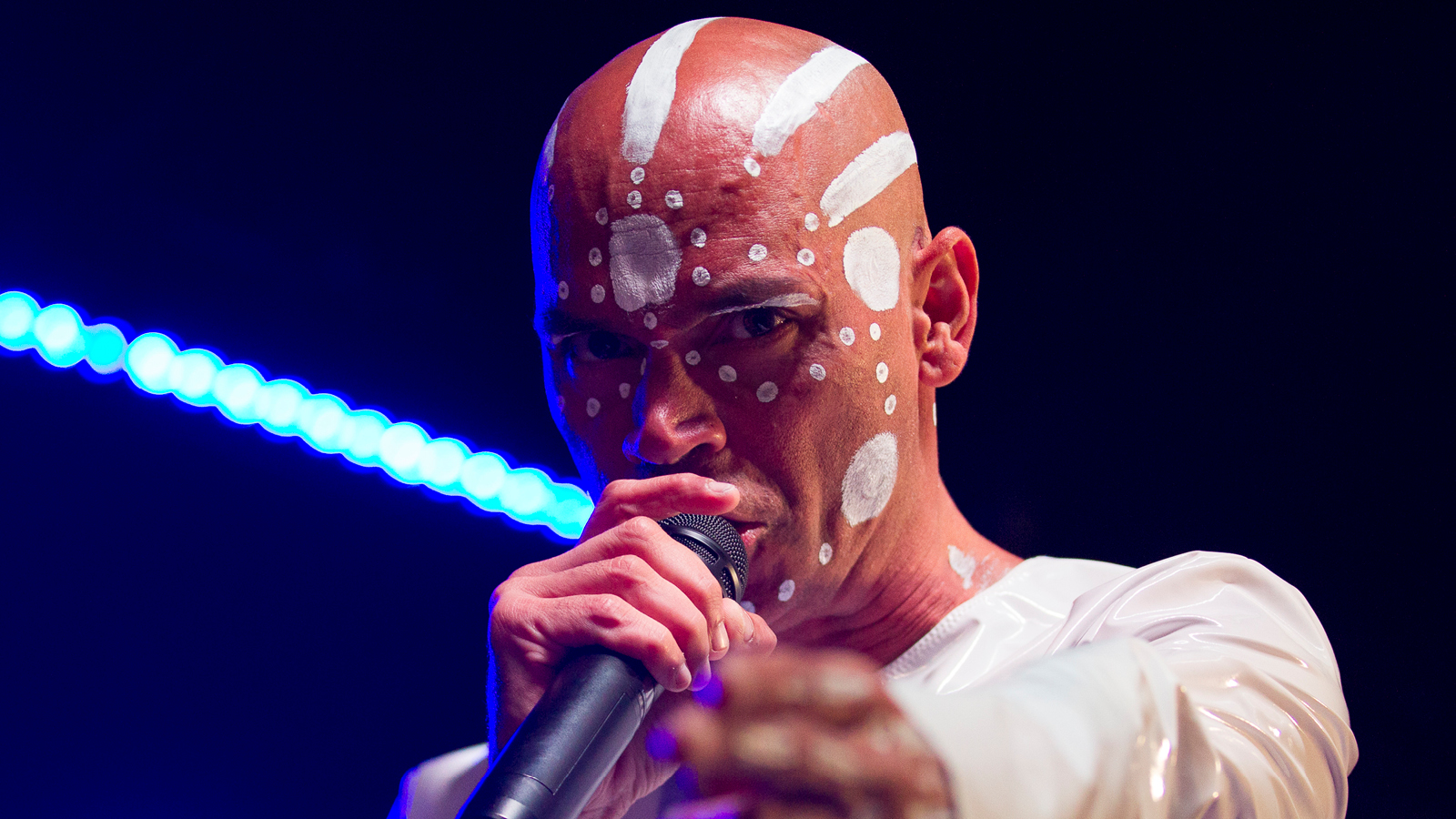

At this year’s Homeground, I’ve invited First Nations artists from New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and Canada to perform along with musicians, dancers, weavers and artists from Australia; it’s a global corroboree where, as sisters and brothers, we can forge a greater understanding across borders with the people that are original owners of lands around the world.

The world-wide dialogue of fear is rising, we need to push an alternate rhythm, movement and positive change – with grace and respect. We know it’s good for our brains and it invigorates Australian culture and promotes stronger connections to country.

Start to listen, and your body will catch the rhythm.

Article originally published in the The Guardian Australia on 7 Oct 2016.